The Worthing Plot

A novella

The Worthing Plot RUFUS KNUPPEL

I have come to destroy you, I repeated in the breathless moment between my striking of the ivory-inlaid buzzer and the darkening of the brass-rimmed peephole. I posted myself before Isabel Worthing’s door (apartment 8C in 130 East End) at exactly two minutes past eleven, and, expecting that devil woman to greet me, I startled when a diminutive Filipina in a white apron opened the door instead.

“Hi sir.”

“Hello. I’m Jack Gardner from The Lyndhearst Review. I’m here to interview Mrs. Worthing.”

“Yes sir. Come through,” the woman instructed, bowing her head to me.

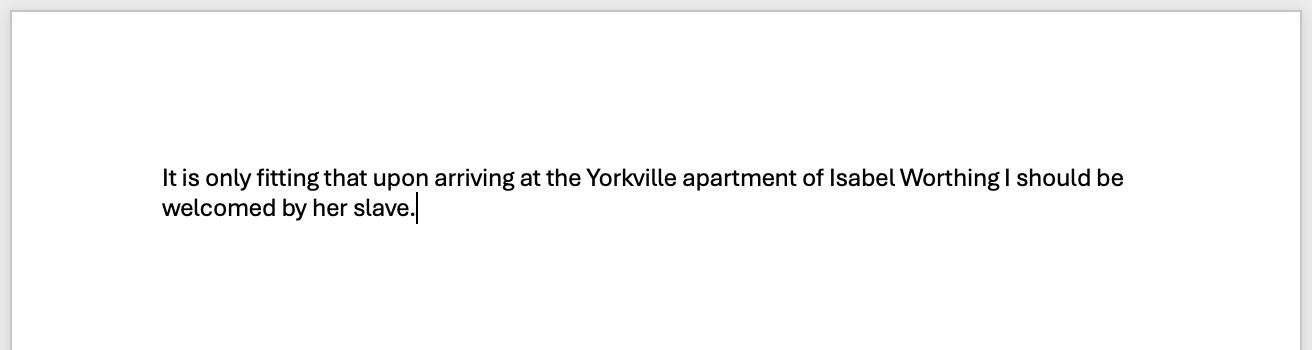

I followed her over a Turkish runner down a dark, slotted hallway. In her right hand she clutched a pair of rubber gloves. Inspecting Worthing’s black and white family stagings and vulgar fine art, the first sentence of my story suddenly surged through me, the establishing image of my bombshell:

Worthing’s poor servant now signaled me to pause behind her in the hall. We stood at the precipice of the great room, wherein the morning light above the East River and Carl Schurz Park poured over a vista of Queens. I was not perturbed, for three years of liberal arts education had taught me to expect that my enemy should be rewarded with a view.

“Mrs. Worthing the young man is here to see you,” the woman said to her master.

“Thank you Maria, he can come in.”

Maria shuffled by me, scurrying away to resume her labor. Worthing was seated on a cream-colored couch, from which she rose, revealing her stark height, the rectitude of her hair, and the right angles at the corners of her black velvet blazer.

“Hi Jack,” she said, extending her pterodactyl digits toward mine.

“Hello Mrs. Worthing. Thank you for taking the time to talk to me.”

“Please — call me Isabel — I’d like that much better. You’re a fellow Reviewer after all. I did try searching for your work online, but I couldn’t find anything — I assume you’re new to The Review then?”

“Yes. I just joined the staff this year.”

“Ah I see. And I trust all was okay with your trip.”

“Yes. I took the Lyndhearst Coach. I find it rather productive and pleasant.”

“Hm okay. Well — tell me a bit about yourself.”

“I’m from Chevy Chase, Maryland. I study History and Economics at Lyndhearst. I want to join public service after I graduate, preferably either legislative politics or state department work. I’m a junior, so I have two years left.”

“Less than that really. Where were you at school in D.C.?”

“Friends.”

“Oh excellent. And what do your parents do to land them in Chevy Chase? Perhaps I know them.”

“Oh I don’t think you would. My father is an ophthalmologist.”

“Well try me, I’ve spent a lot of time down there.”

“Dr. Stephen Gardner?”

“I don’t know him. Maybe after our conversation today I can put you in touch with some people in those sectors you mentioned. They’d be pleased to see The Review alive and well. There was a dark moment a few years ago when the alumni thought it was good as dead. But it seems you’ve resuscitated it, and with the right spirit too. In fact I recently met your editor at a conference in Washington. Liam Mogul?”

“Yes I know Liam — but only a short time really, and only in a professional capacity. He’s our senior editor.”

“Yes — well Liam’s an interesting guy. He was chatting with me about wanting to join the navy.”

“He’s a serious patriot.”

“It seems you are too Jack, considering what you’ve told me about your interest in service and your involvement with The Review.”

My god she was relentless. Her stalking eyes would not release their fangs from my face.

“Yes I feel that there are certain values I ought to protect with the tools made available to me by my privilege.”

“That’s very good then. Would you like some water?” she said, leaning forward over the glass coffee table to retrieve the ceramic pitcher, already prepared for our meeting. She poured my glass first and then her own, never glancing to confirm my approval.

“Is it alright Mrs. Worthing if I use my phone to make a recording of our conversation?”

“Oh absolutely — and really do call me Isabel please. I hope you don’t spend too much of your life on that device. I’ve had to restrict my kids. It got out of control. It’s a horrible parasite among you young people. Just as bad as weed or alcohol for children. Rotting your brains. It’s awful.”

I removed my phone from my jacket pocket as she droned. The apartment was not hot, in fact the scent of refrigeration flowed from some distant room, but I worried I would begin to perspire in my turtleneck if I did not shed my outer layer too, so I took off my coat and folded it into my lap. Worthing’s velocity and her square, impenetrable ramparts foreboded the anguished siege ahead.

“Here — you can rest that on the chair beside you,” she said, guiding my eyes with her finger. “It’s very smart. Boys your age don’t dress like that these days.”

“Oh thank you,” I replied, allowing a second of silence to pass between us. Worthing cracked her hyena smile. I placed my jacket on the zebra print seat beside the orchid and the phone on the coffee table between the water glasses. I opened my voice memo and pressed record.

My name was not Jack Gardner. Jack didn’t exist. My real name was Milo Gardner, and I wrote for The Lyndhearst Jacobin — not The Lyndhearst Review (as I had told Worthing over email). The previous night, the editorial had gathered to rehearse the details of my avatar at The Jacobin’s headquarters on Main Street. We worked under the cover of night to develop my Reviewer persona, blinds drawn. On November 18th, I deployed to Manhattan, departing my sleepy hollow that morning on the dawn coach. Now the trap was set. The Worthing Plot was a go.

A week before the operation, the launch of My Bravest Years, Worthing’s memoir about her time at the College, had lathered campus into a state of turmoil. Isabel Worthing was Lyndhearst’s most eminent middle-aged alumna. As a student, she had been one of the early staffers of The Review, a dissident Clinton-era proto-fascist journal comprised of the College’s conservative dregs. Then she matriculated to Harvard Law, clerked for Justice Kennedy, and served under the White House Counsel for Bush. That was her bureaucratic career, when she was a guerrilla elite, moving silently in the great marble jungle of courts and lobbies and corporations. Then she married a financier with no public record besides the title —

— on the website of Aphrodite Capital, moved to New York to start a family, and went dark.

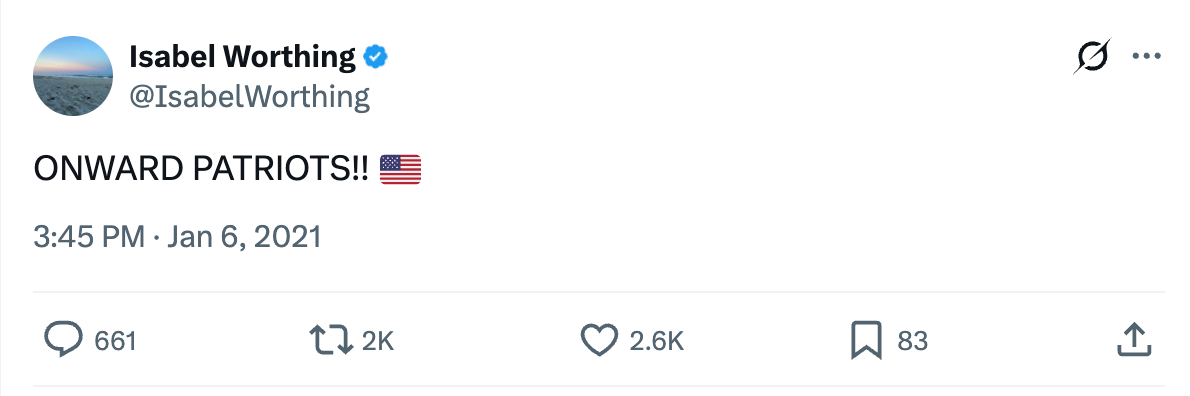

In Trump I, her kids having grown through the Obama terms, Worthing took on prominence as a legal talking head for cable news shows, commenting on the judicial fiascos of that fateful term: the Mueller Hoax, child separation, the first impeachment, etc. She was an early pundit for the grievances of justice which would precipitate vengeance on the American system. Already a party favorite, she found national fame as a detractor from pandemic regulations — the minor TV celebrity that she was — posting videos of herself violating lockdowns and mask mandates and railing about authoritarian infringements on American liberty from the quiescence of her East Hampton patio. Worthing’s punk bourgeois reputation in MAGA circles ballooned as she performed ever more vile and reproachable stunts online, uprooting BLM signs from Long Island lawns, dead-naming trans activists in on air debates, and predicting Biden would be “our most retarded President to date.” On January 6th, she tweeted:

The aggressive unravelling of Worthing’s decorum led to her suspension from one channel and her resurrection on another.

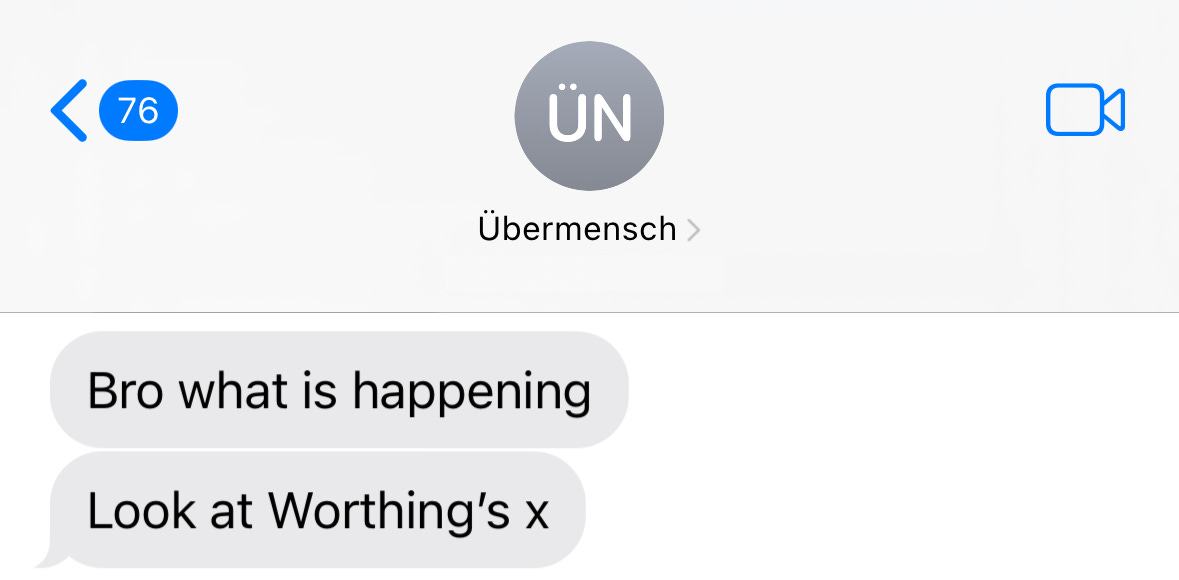

Anointed a martyr of the inflamed, post-stolen-election Right, the contradictions of Worthing’s debutante populism only further illuminated her stardom. The climax of her nubile political career manifested in a futile congressional campaign for New York’s 12th district in 2022, that slice of the Manhattan upper crust in which the stiff and elegant provocateur both lived and remained most patently reviled. The maneuver was Worthing’s hideous masterpiece of democratic abuse, a candidacy verging on performance art — designed like a solvent to erode any varnish of the sacred that adorned the American political project. She nicknamed Jerry Nadler “the Fat Incompetent Jew” and Carolyn Maloney “the Grand Wizard of Woke.” A rumor spread that the parents’ organization at the preparatory high school which the Worthing children attended in the Bronx was referring to her in their group chat as “The Cannibal” and trying to secure a restraining order to bar the madwoman from campus:

Worthing lost the race in November — not without solidifying her status as a titan of the New Right — and promptly retreated into the hibernation of the private sphere to regroup both her wits and her coalition.

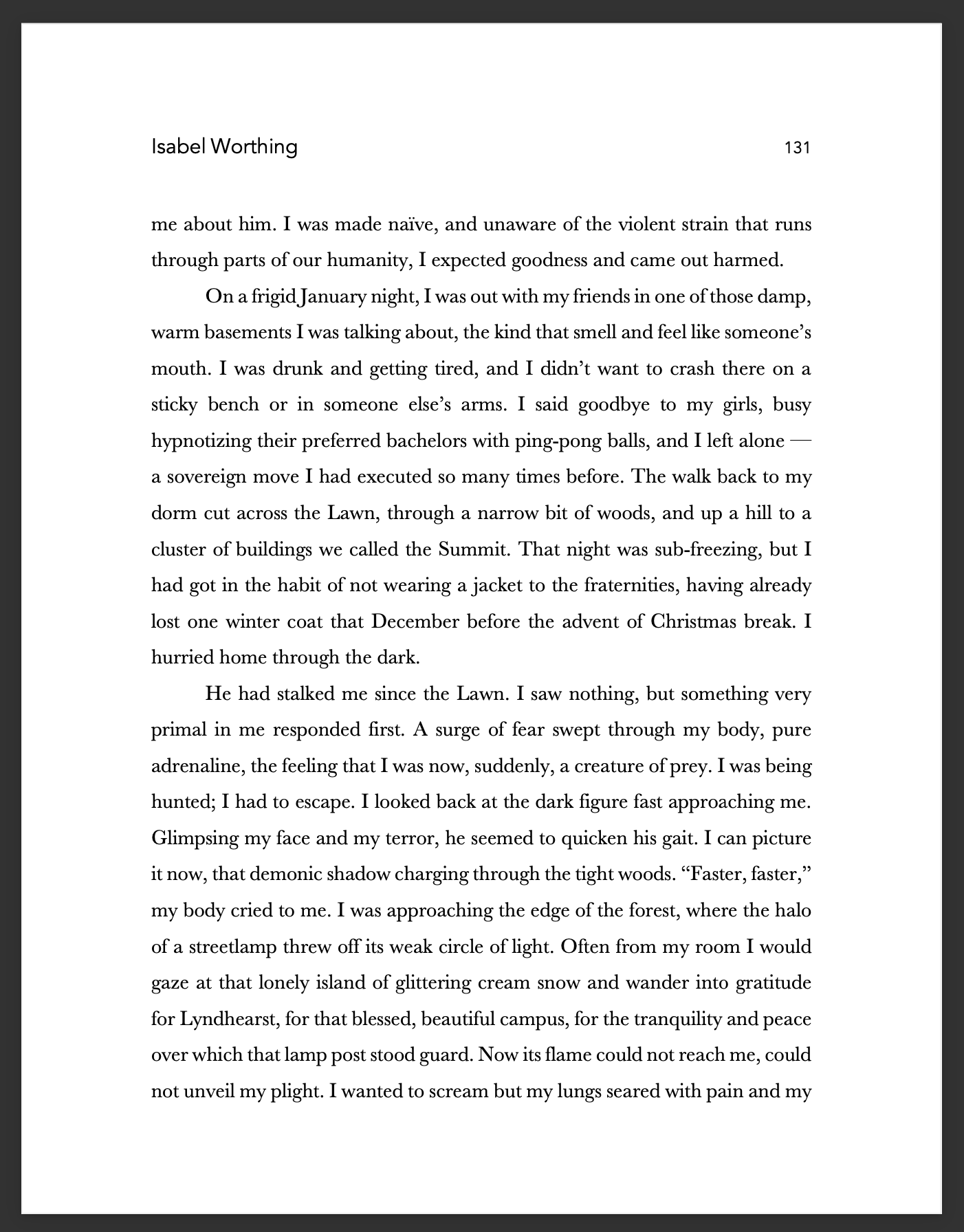

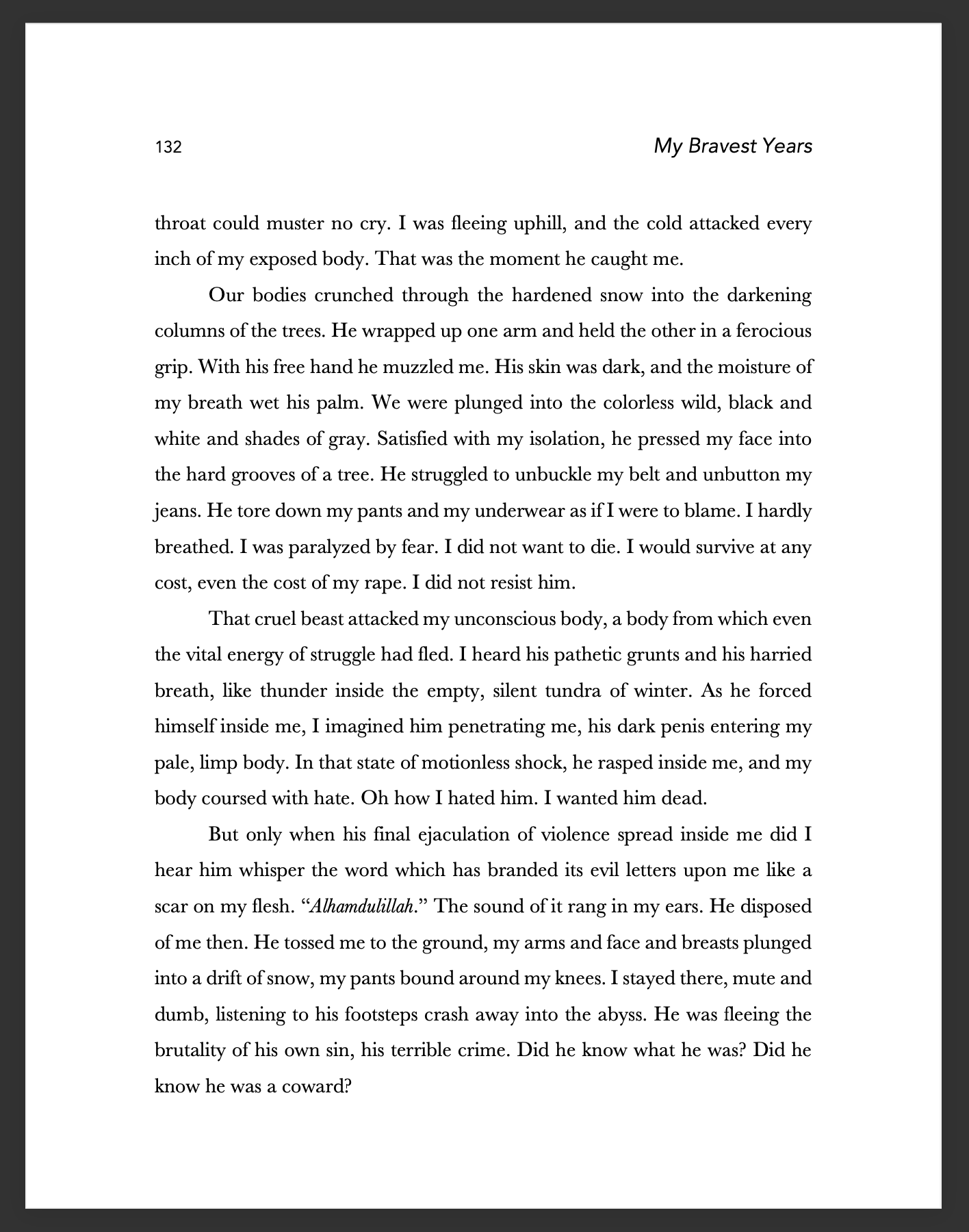

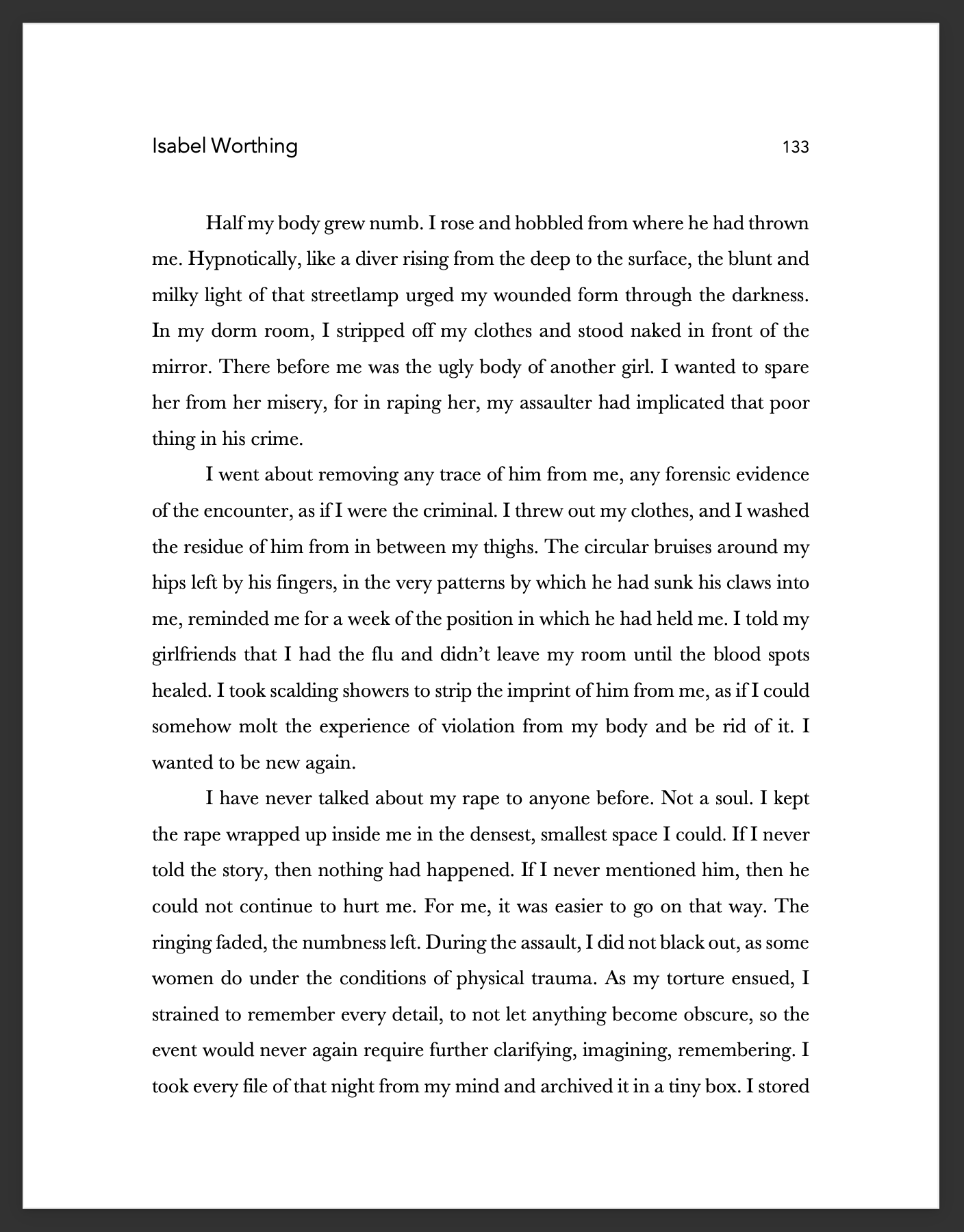

But now the big splash had arrived, My Bravest Years from First Principles Press, Worthing’s memoir three years in gestation. On November 10th, the day before the book’s release, The American National had published an early access review, titled “The Starlet Speaks,” in which it was revealed that Worthing’s memoir featured a shocking account of her alleged rape at the hands of an anonymous Muslim international student on Lyndhearst’s campus in 1994. An electronic galley copy excerpt of the above soon floated onto Twitter (X), the vital section of which I shall print below.

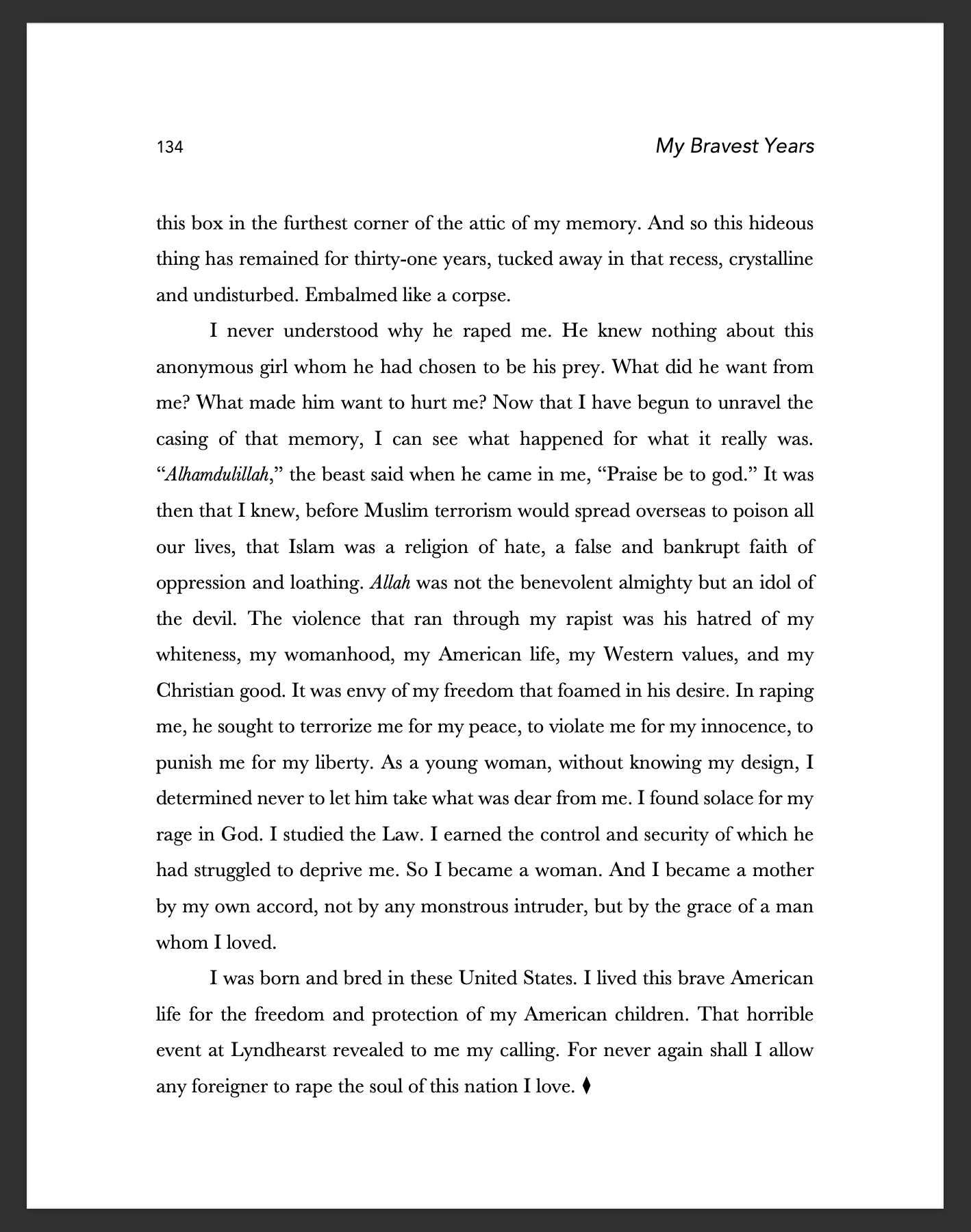

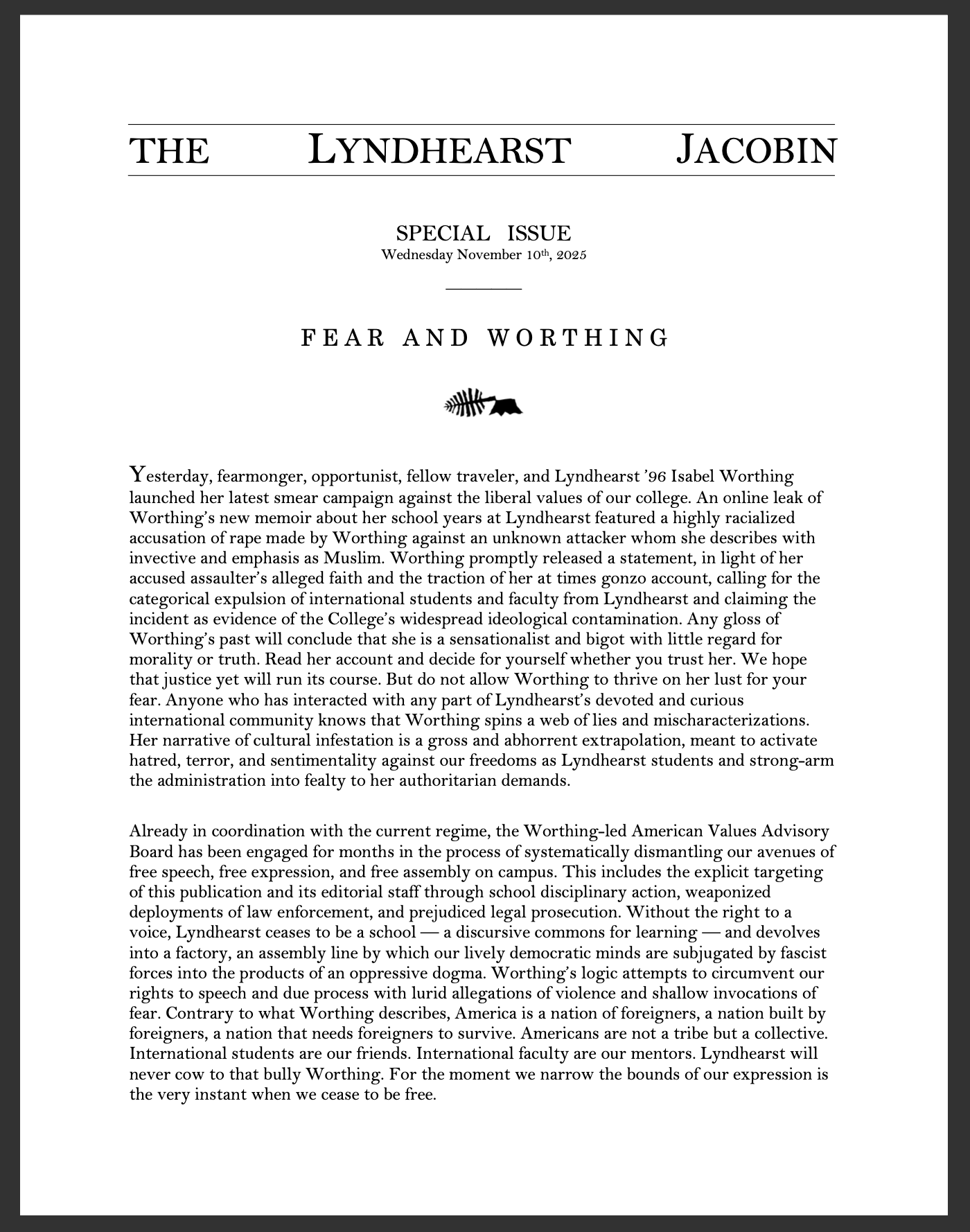

Was the excerpt real? Had Worthing made it up? No one knew. The internet exploded, as it was calibrated to do from time to time. Worthing, who had been scheduled to visit Lyndhearst to tour her mysterious new book, pulled out from the event, releasing the following statement regarding her resignation from College-related activities, including her shadowy role as chairwoman of Lyndhearst’s recently inaugurated “American Values Advisory Board” — a committee mandated by concessions laid out in the administration’s memorandum titled “Eliminating Lyndhearst College’s Radical Rebel Network,” a document in which The Jacobin was cited eight times for “fomenting violence” and “harboring felons, trespassers, violators of hate speech, and potential radical terrorists who disdain both the rule of law and American democracy itself,” among other grievances and crimes connected with Gaza-related activism and other sinisterly intersectional protests. Worthing posted the following on X:

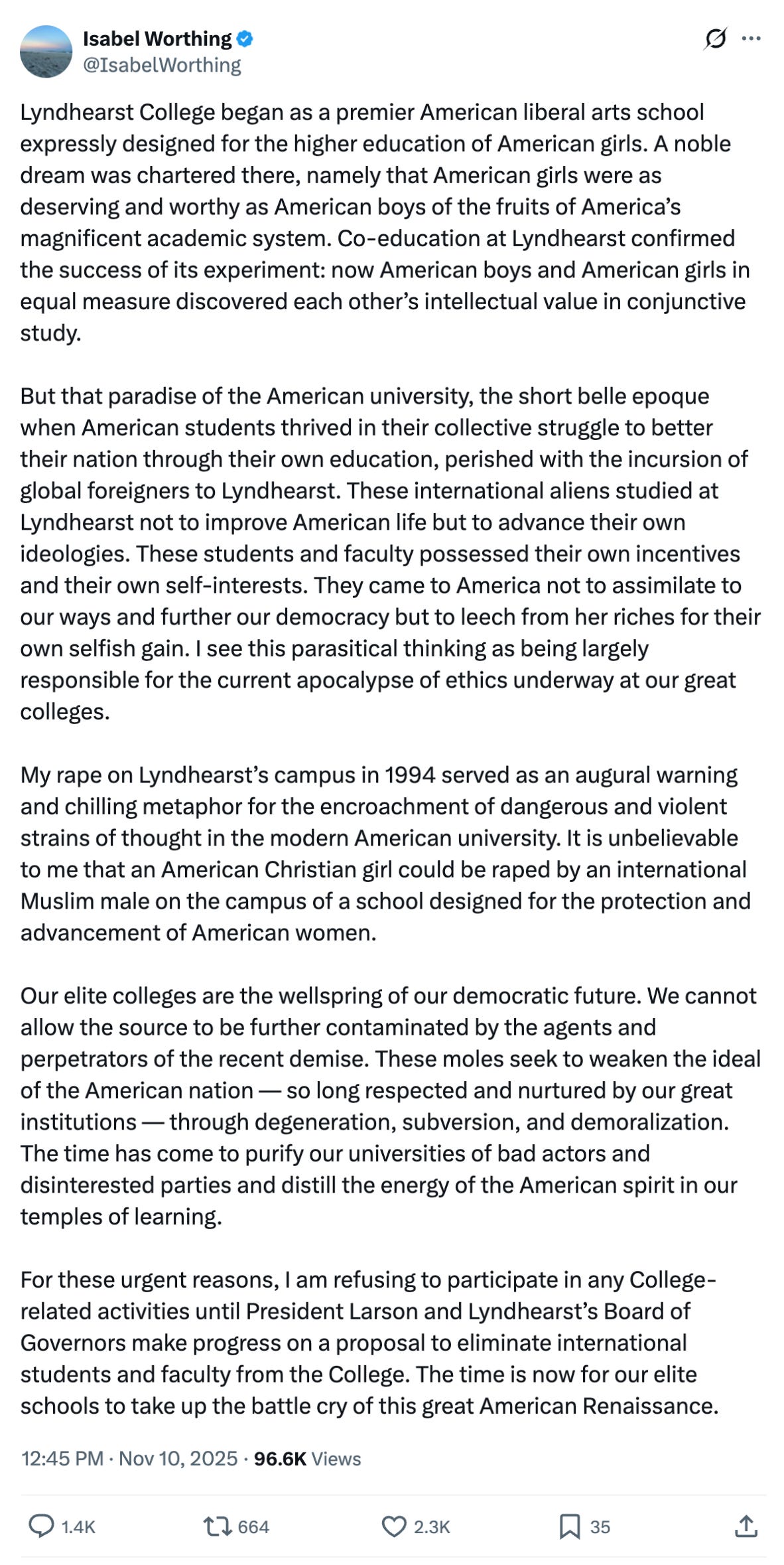

President Larson, the poor woman, had only months before supplanted President Sperling, herself engulfed in the flaming pyre of the ungovernable mob. Even the socialists had recognized that Sperling’s hands were tied. Now Larson had inherited an even more impossible situation. Two months prior the new president had capitulated to executive demands in a plea to recuperate the federal funding which Sperling had disavowed. President of Lyndhearst was a job for a suicide bomber, not a bespectacled professor who had spent the first twenty years of her career in the catacombs of the National Archives counting casualties from the Spanish-American War. We loathed and pitied her, but Larson could no longer retreat to her stacks, the clamor of the internet deafened all. That evening she blasted out a campus-wide email:

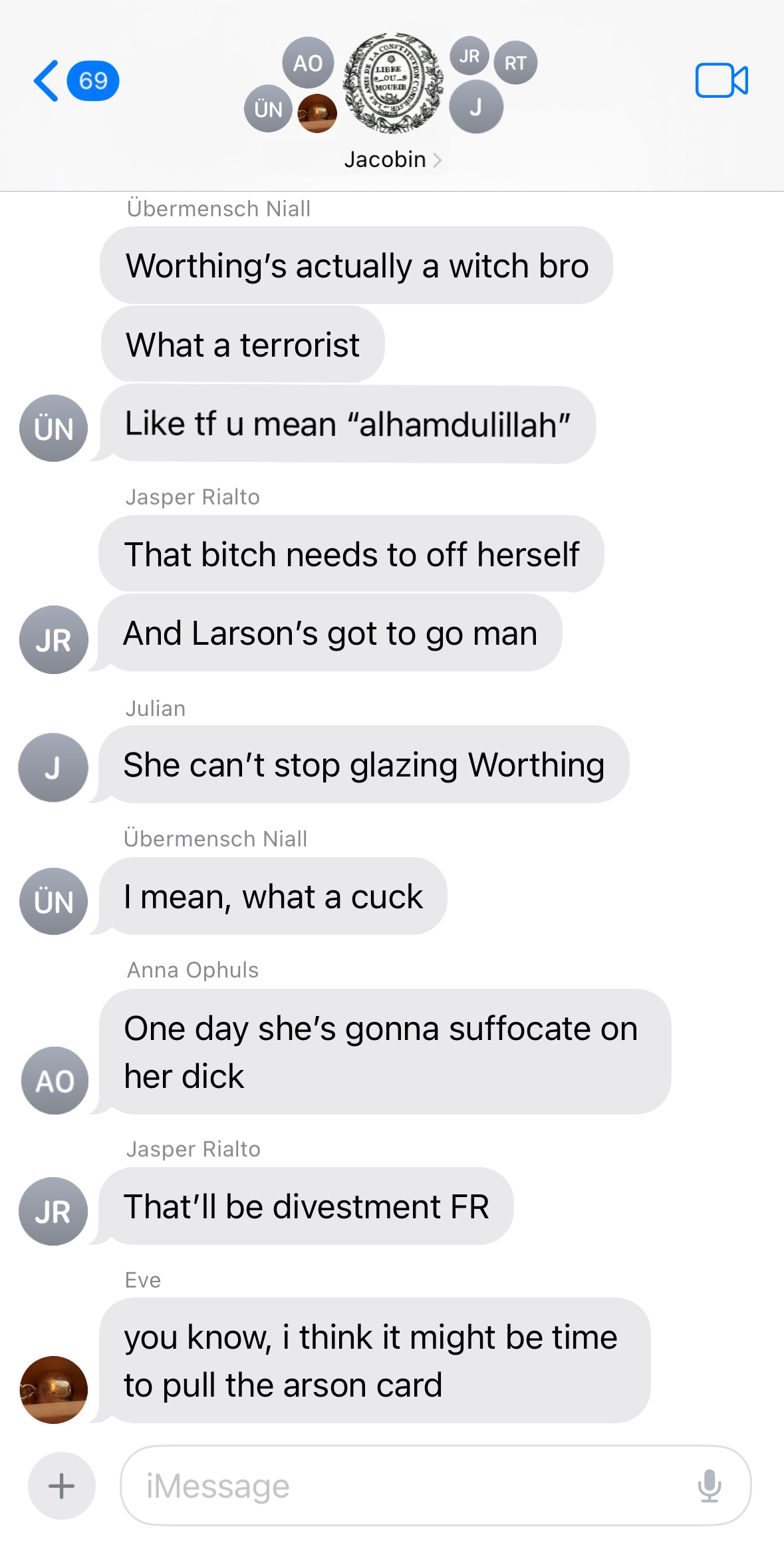

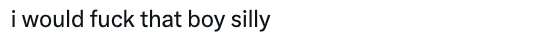

In that dark hour, messages from The Jacobin’s editorial group chat spawned so rapidly onto my home screen that I feared my phone would self-immolate.

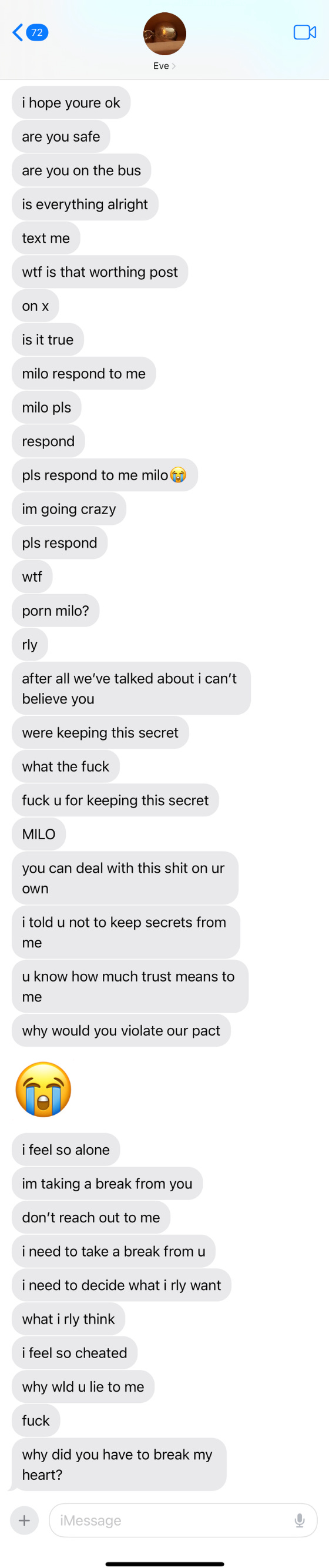

The last message was from Eve, our copy editor who texted in demure, ironic lowercase, by no coincidence meine Freundin.

Oh Eve. She was perfect in the abstract. Her puma eyes with the black serifs. Her suburban features. Her revolutionary zeal. I forget now what denomination she sprang from — Jesuit, Quaker, Swedenborgian? It was all the same to me. Weird evangelical shit. I didn’t know those people still existed in the U.S., but Eve assured me that they did. She’d arrived at college wearing a cross and undergone a bad bitch, alt metamorphosis, like in Grease. Grease was her favorite movie. She told me she had mapped out her transformation in high school when she was a cheerleader in Illinois. She would often ideate herself onto older girls of the avant-garde she found on Instagram or Pinterest. She kept a second secret self in her head — the real Eve, not the dysmorphic girl in the mirror — that she would work to develop beneath her normie shell. She would spend all night online shopping for her future persona. She read the Marquis de Sade and watched Rohmer movies and listened to SOPHIE on the bus to prepare for her transition, her difference. That kind of thing was the freaky, mysterious side of womanhood that a straight boy at a former girls’ college could not resist the scent of. The salivating possibility of manipulation at the hands of a radical female psycho. The idea of being lectured about David Lynch and capitalism by a human with breasts. The mercurial desire and the volatile compounds operating in her XX hormonal alchemy. The pale, vampiric skin on her tall legs radiating through her dark tights whenever she crossed her thighs in disapproval. Eve’s dream was to go to Istanbul and ride in a hot air balloon over the minarets, and when I first flirted hard with progressivism my sophomore year, she seemed to me the bejeweled oracle of the benevolence that socialism had in store: a bellybutton piercing, a semi-ironic stick-and-poke tattoo, and the teachings of Karl Marx. Her name was even Eve.

Eve drew me into The Jacobin when she was editing for the female-only Joan of Arc Review, a publication which eventually dissolved because of intramural lesbian drama. We were introduced at a Leftist mixer that I attended with my friend who could not go five sentences without mentioning a YouTube video that he’d watched about Watergate. Eve told me that if I wanted to get serious about my politics I should start writing for The Jacobin. That was all I needed to hear to take her to bed. De-clothing Eve was like unwrapping a mummy, but sex with her was a living, vocal thing — the jingling silver jewelry and the metallic taste of that bellybutton. Eve was rapture. Eve and her apple.

That spring we only hooked up if we coincided at a party. We were always slightly wasted, and I never got her number. I looked at her LinkedIn profile picture maybe eight hundred times in the month of May. “I like it like this, like we’re in an old-fashioned affair,” Eve said, though I could hear the lie on her tongue. These rendezvouses became more frequent, and I started secretly stalking her out at functions and pretending our intersections were happy miracles. Eve did the same. After sex, we would chat a little about politics, for no reason other than awkward habit. What I was working on for The Jacobin. How things were falling apart at Joan of Arc. The atrocities of the world. The pinball machine of modernity. Slithering out of technology. I took some pride in the fact that when we met Eve was in her “lesbian phase” and that my heterosexual prowess turned her to the cause. “I can’t believe I used to be so afraid of dick,” she told me in one of our post-coital chit-chats, “now I want it all the time.” We would gossip about Lyndhearst friends too, and then one of us would slink home like a ghost. I would often wander the nocturnal wasteland listening to atmospheric melancholia for hours after our encounters. It was the loneliest I ever felt. I can’t really say why.

In September, Eve jumped the sinking ship at JOA to join The Jacobin. At our Bolshevik-themed homecoming party we got so fucked up on imported Polish spirits that the veil could no longer hold. I told Eve I wanted to date her and she cried with relief. I woke up next to her in the pink dawn light and pressed my thumb against her tear-smeared eyeliner. I listened to her quiet breathing, that precious creature taking shelter against my chest. I didn’t stir. I only watched her. And hours later, when I woke again, I found her watching me, just the same.

As Eve and I started dating, The Jacobin began to overwhelm my school life. The kids who wrote there seemed to me the only people at Lyndhearst who actually cared. They took their reading seriously, but not in the lame way. They believed in erudition, in writing and history and culture and art. They were not okay cruising through the world on aesthetic autopilot. They felt there were urgent questions to living which demanded immediate answers. They wanted to right where they saw wrongs. They justified their pessimism and lionized their idealism. They were hungry for travel and the city and for altered states of consciousness and the limits of human experience. They abhorred routine and stagnancy. It was posture, of course, but the right posture; everyone at college was posing after all. The smartest ones despised centrists more than they hated the Right. The horde at Lyndhearst, they told me, were forfeiting their sovereign will to influence the circumstances of their own beings by becoming sheep; it was a lazy, repugnant existence, being a follower; I agreed with them. The people I knew at school who thought that way — who thought the world ended just about as far as they could see — were apt to lead the most mundane and inconsequential of lives. I wanted to understand things in all their subterranean and sublime dimensions. I wanted to open my mind. I wanted to know what Jasper meant when he spoke about “the chthonic impulse.” These guys had to be onto something. I just felt it. The Jacobin electrified me.

Our scrappy little publication scrounged money from Leftist alumni and progressive support networks to lease an office space downtown and pay for monthly print issues. In part those funds entered a narcotic laundering scheme to funnel weed, coke, and ket to the nose-hungry and queer-curious Jacobin staff. I was living with the other male editors that fall in an old, dilapidated Victorian home off-campus that had been bequeathed from one socialist to the next for fifteen years running. You can only imagine the state of the place: we were running a fruit fly experiment. We’d all hang out together, get fucked up, go on our phones, ingest food dye. Eve would come over almost every night to chill — we spent so much time conjoined in the house (which everyone called “Plato’s Cave”) that our friends denominated us as “Meve,” an epithet I hated but Eve adored. I thought it signaled a dangerous dose of codependence and the worrying fact that our private relationship was quickly being subsumed into the professional life of the publication. Eve said I was thinking too hard, “Meve” was a cute nickname, a term of endearment employed among friends to express intimacy. I sensed we were both right.

I also came to realize in prolonged conversations with Eve out walking in the Berkshire hills that her total rebellion against that past life of hers had sublimated into a belligerent optimism in the Left. For example, Eve believed that a Marxist utopia was a probable reality within her lifetime, a future in which, once absolute socialist government had seized the means of production and established cooperative control, the shackles of class and state would fall away into collective bliss, which I thought demonstrably preposterous considering the authoritarian failures of communist governments over the last century and a half of regime implementation. Even if the material conditions for that revolution presented themselves (which they certainly could not without significant bloodshed — but we were already operating within a fantastic hypothetical considering the democratic backsliding of contemporary times), I argued our state of nature was far more Hobbesian than Eve might care to believe. But whenever we debated teleology Eve would always end up placing a finger on my lips and giving me head on my mattress, that sorry bed of mine which often lay bare on the floor of the attic in that uncleanly house. Look around at this dirty fucking place — I wanted to tell her, I wanted to prove my point — is this shit hole not evidence enough of Marx and Engels’s blind spot? But she wouldn’t listen, she just kept licking away with her magic mouth, that apolitical vortex.

The others at The Jacobin had all read more widely and rigorously than I had. It made me insecure, even in casual debate; I feared I might tumble over in some conversation about the Counter-Enlightenment into a gigantic hole disguised by palm leaves within my corpus of knowledge. I worried I would expose myself as an imposter in their clique, or worse, a fool. That was why, every now and then in the throes of Eve-induced pleasure, I would cock my head to read the spines of the unread theory tomes that stood lined like toy soldiers on my desk — leftovers from past editors or gifts from Eve and older Jacobin friends. I was exhilarated by the promise of their knowledge and disappointed in my shallow edification. I was too lazy to be a great thinker. The Mass Ornament...oh I’ve heard great things, I’ve heard it will change my life, I’ve heard it’s the most slept on Frankfurt School text. That should be next. I stopped. Are you fucking serious, Milo? I was not reading after all, I was busy getting felatiated by this sexy, clever girlfriend of mine. The one with the breasts and the bellybutton piercing that every incel on staff was ogling. I was doing fine.

I did have one big secret I was keeping from Eve though. I was a gooner — though I stretched that wonderfully elastic word in my head to encompass something rather tame: I wasn’t addicted to jerking off per se, and I certainly wasn’t after the meditative pre-orgasmic Zen state that the professionals achieved, but the idea of giving up my porn habit was about as traumatic to me as the prospect of someone stealing my Halloween candy had been when I was nine. The problem was that Eve considered porn to be brutally anti-feminist. She would rail against the exploitations of the porn industry and the horrible violence that was infecting the minds and cocks of young men everywhere, these hopeless adolescents lured by the fake shit on their phones that reduced women to flesh puppets — “pornbraining” was her term — and it took every neuron in my pornbrained brain to affirm her sentiment and diffuse the nuclear bomb that would inevitably erupt when she asked me: “Have you watched porn Milo?” What would I say then? Oh god — it was too gnarly a thing to imagine; I harbored my secret because I feared that moment. The paradox of the situation was that Eve said all these demeaning things about the men who watched porn while reading a ream of smut a week on pirated e-Book websites. In these trashy novels, the protagonist would get fucked in all her holes by a cosmic prince with a twelve-inch “velvet shaft” and hulking, delicate wings. I knew about this habit because one day I stole onto her computer and found that particular chapter about the prince in her search history nestled among many, many others of its ilk. Sure it was hot, but men with wings were not my thing. And while I didn’t take her erotic reading as permission exactly to keep watching porn on long breaks to the bathroom which I disguised as stomach problems, I did view Eve’s clandestine habit as a kind of reciprocal indulgence that would make our later confrontation on the subject more palatable. She didn’t suspect me, I didn’t think, though she said I should go see someone about my digestive issues. Watching the porn knowing how much Eve condemned it made me feel guilty, which in turn made the masturbation more illicit. I liked keeping a secret.

The Monday night before the Worthing debacle though, Eve and I had had a bad fight. She spent too much time on her phone. Well we both spent too much time on our phones. I was trying to get her to talk to me about a reading I was doing for my “Fascism as Prelude” class on Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. But Eve didn’t want to talk about the banality of evil. She was glued like a moth to the blue light pulsing off her iPhone.

“Can you get off your brain rot and talk to me?”

“It’s not brain rot. I’m reading.”

“No you’re reading Twitter. That’s not reading. All this fucking screen time and slop. It makes me so fucking claustrophobic.”

“Oh really. Like you don’t spend half the day on Twitter.”

“At least I don’t scroll while you’re talking to me. At least I put my phone down long enough to open a fucking paper book and do a reading.”

“Oh yeah? And when’s the last time you finished a book Milo? — That’s what I thought. Leave me the fuck alone and get literate before you lecture me about my phone usage.”

“You sound like a heroin junkie.”

“So do you.”

“I know.”

“Yeah I know too — that’s what we are.”

In that moment of desperate awareness, Eve threw her phone at the bookshelf, where it collided with my immovable copy of Ulysses and came crashing down onto my bowl, which shattered meekly into infinitesimal glass particles and sprayed a miniature plume of marijuana ash all over the floor. Bated silence filled the room with fumes.

“Fucking hell Eve.”

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to. I shouldn’t have overreacted. We’ve just been in this room for the past five hours. And your fucking bowl shouldn’t have been on the floor anyway.” I shut up. “Oh god — we’re such slobs.” She started to cry. I looked around the place, my prison cell.

“Okay come on baby. Let’s go for a walk and worry about it later. We need to move. Get out of the mud.”

“Alright,” she said, wiping tears, “you’re right.”

We threw on our big coats and shuffled wordlessly down the three flights of stairs to the moonlit porch. The glacial autumn air seared my boiled nervous system. I gazed at the illumined steeple of the Lyndhearst library tower. Eve scurried out the aching screen door. We held hands and stood silently in the afterhours campus still. Then I reached over her tiny person to hook her little shoulder. She ensnared my waist with both hands in a wrestling grip. And off we went, sauntering down to the river — our chosen place.

“What would I do without you to drag me out of my hole,” Eve said, clutching me closer to her as her hot breath steamed into the night.

“I’d rather you drag me into your hole Eve.”

“Oh Milo!” she said, pressing her face into my shoulder.

We were two idiots in love.

The Worthing pandemonium called for an emergency tribunal. Our editorial council gathered eagerly at the Jacobin offices. The gusty night deepened the Gothic campus mood.

“My intelligence tells me that The Review is planning on running some kind of pro-Worthing flyer by tomorrow morning.”

“Who told you that?”

“Will Donovan. His roommate is friends with Charlie Chapman [managing editor of The Review].”

“Well do we have print supplies here in the newsroom to run sixteen-hundred copies?”

“I don’t know. I’ll check the closet.”

“The library printers are closed.”

“We’re past town curfew too.”

“Okay — I found a fresh box of paper — that’s twenty-five hundred pages.”

“And ink?”

“We should be fine if we print black and white.”

“Okay well I say let’s draft a memo and run it alongside The Review.”

“Me too.”

“Aye.”

“Yes captain.”

“Alright — let’s fucking go then. Harpoon the bitch.”

There were seven of us there that night in the newsroom. Julian, editor-in-chief. Jasper, managing editor. Anna, design. Niall, content. Robbie, editor emeritus. Eve, of course, copy. And me, senior staff writer. What berserk forces had acted to congregate that motley crew of American socialists in Lyndhearst? The room hummed with anger and energy. We labored late into the night on a draft. At three we polished and printed the text. At five we had delivered a statement to every doormat on campus.

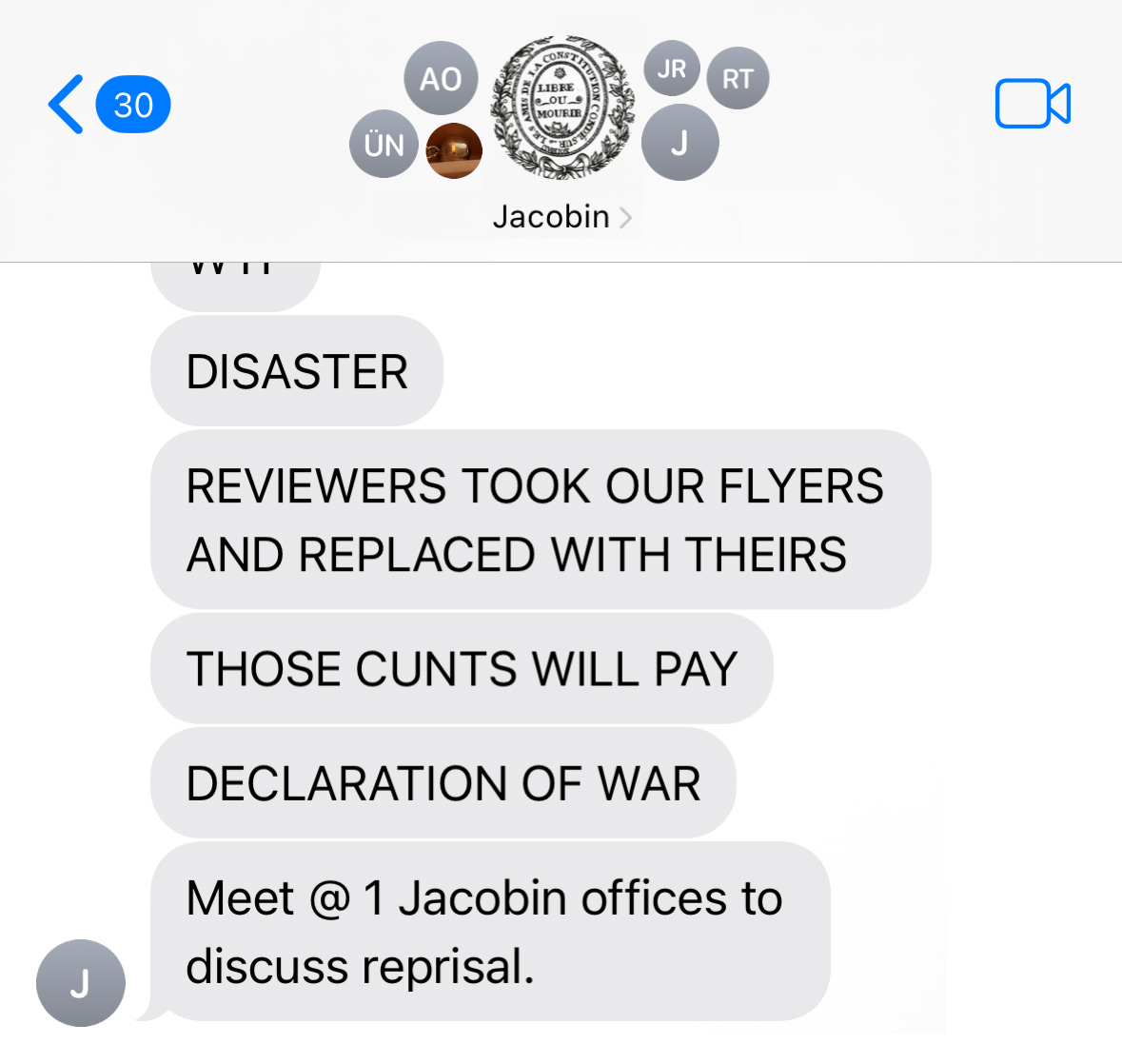

Only next morning at midday, when I woke next to Eve — nervous and sleep-deprived with a headache that felt like an icepick in my skull — did I become aware of the terrible thing that had happened overnight.

I then opened Colleger, the app everyone at Lyndhearst used for campus social media, and saw the top post of the day — 553 upvotes in two hours —

“Fuck. Eve. Wake up baby. Bad news. Eve?”

“Yes? What is it?”

“Oh fuck. Bad news.”

“What? Should I be scared?”

“I don’t know yet. Julian says that last night The Review went around after we distributed the statements, gathered up the flyers, and replaced them with their own.”

“Oh my god, what the actual fuck.”

“Heterodox my ass.” I scrolled deeper into the comments on Colleger.

“So what’s happening now?”

“Julian called a meeting.”

Twenty minutes later we arrived at the Jacobin offices nursing two tall vanilla lattes. The rest were there already, disheveled, looking like they’d slept the last week on the concrete floor of a bomb shelter.

“Welcome to the situation room.”

“Hi.”

“We’re discussing what should be done. Niall thinks we should protest outside The Review. Jasper thinks we should publish a response condemning them —”

“I said I think we should produce some kind of parody flyer formatted like a mock-up of The Review where they apologize to us for their bad behavior —”

“Oh I like that.”

“I said I think it’s too tongue-in-cheek. This whole thing is too serious for comedy. We need to stab them in the chest.”

“Well I agree with that. Can I be honest?”

“Yes Milo. Be honest.”

“I think we need to totally blindside them somehow. They’ve played dirty. They have all the leverage. The response can’t be a slap on the wrist for not acting by the rules. That’s middle school. We’re all adults here. We’ve got to kick them in the balls. We need something extravagant. Something unexpected.”

“Okay — like what?”

“Like fucking — I don’t know. Like — I don’t fucking know.”

“Like do our own hit piece on Worthing somehow.”

“What do you mean?”

“Like real reporting where we nab her for some bad shit she’s done and discredit her. Disgrace her somehow.”

“Okay — I need to hear more though.”

“What about one of us stalks her out somewhere? Sees what she’s up to? Expose some criminality? I’m sure she’s moving in some corrupt, fishy sphere.”

“No no guys — I’ve got it.”

“What?”

“One of us goes undercover as a sympathetic Reviewer, gets into her house, her inner world, records it all — and we write some vicious profile about Worthing — all the shit we always talk about — the front of her populism, her subliminal hatred for the masses, her weird personal life that no one knows anything about, how she’s fucked up her kids by being a selfish mother. Her husband’s cheating on her, she’s cheating on her husband, I don’t fucking know. That woman is too fucked in the head not to have some baggage hiding in plain sight. We’ve just got to get her to spread her cards, get her to open up, admit she lied about the rape for clicks. Get her to say that she’s an opportunist, she’s the puppeteer, that it’s all for her own gain — yeah, I think this is it.”

“Do you think she would buy that front?”

“Yes I do.”

“Who would go then?”

“I don’t know.”

“I think it should be Milo. He’s the most nimble and the most conservative-looking. He could be a Reviewer you know, the old-money, legacy type.”

“Why thank you.”

So we got to work. I did my reading — got my hands on a copy of My Bravest Years and filled the memoir with marginalia. I went to Draper Library and requested Worthing’s college file — under Adams. I found her old articles for The Review in the archives. They astonished me honestly. Even at that young age Worthing was a coherent, conniving writer of remarkable rhetorical strength. Her essays so easily coordinated themselves around a systematic thesis. It was no surprise she became a lawyer. But her crystalline sentences had none of that parched legal doctrine. She never bored with stale language; her prose lost none of its vivacity and moisture to her argument. I read her work with bitterness. My god — was I jealous of the young Isabel Worthing?

To reach out to that viper, we had to create a decoy extracurricular email for my persona — Jack Gardner, Lyndhearst ’28. We got her Lyndhearst contact from a friend who had interacted with her through an American Values Advisory Board hearing panel on degenerate course syllabi. I sent the email and held my breath — for seven hours — awaiting a response.

Worthing had devoured the lure. That gullible clown. I skipped home to find Eve watching videos in my bed. I ripped the phone from her hands and attacked her ravishing tits with kisses.

“Ah! What are you doing Milo? Ah!” She squirmed under my weight to grind herself against my leg. “What happened? Tell me!” I had her straddled beneath me as I nibbled on her neck.

“She said yes.”

“Worthing did?”

“Mm-hm,” I said, licking the vein that ran from her collarbone to her jaw.

“Oh baby. I’m so proud.”

“Well it’s not over yet.”

“Oh certainly. But I want to celebrate your victory,” Eve said, running her hand up the erection in my jeans, “I like it when you win.”

Supposedly The Jacobin had become milder in the year since I had started for them. They had been forced to temper after the previous editor-in-chief, Cosmo — legal name Climate Change — had been expelled for storming and barricading himself inside President Sperling’s office while demonstrating alone for his self-fashioned “Lyndhearst Anti-Zionist Divestment Plan.” A Massachusetts SWAT unit had cleared him from the administrative building by repelling from the roof and kicking in the windows. The College had stated that such force had been required against the student because the suspect had posed a significant domestic terrorism threat. They added that there had existed reasonable evidence to suggest that Climate Change had planted ancillary explosive devices around campus.

“I mean Cosmo was a nut,” Niall explained. “He kind of lost his mind that year. He felt he was the only one who cared enough to do anything real. And nothing was coming of it. The administration didn’t budge. It escalated really quickly. He asked all of us to join him for the Sperling raid. None of us would do it.”

“What’s he up to now?” I asked.

“I don’t know. We had to sever ties to keep The Jacobin out of the indictments. I know he was cleared on the terrorism charges, but he got sentenced for criminal trespassing — I forget how much time he served. Now I think he’s back living with his parents in San Francisco. I don’t really know man. He’s gone dark.”

“Damn.”

“Yeah. Shit’s no joke...now I’m remembering that I promised him I would read this Dickens book.”

“Which one?”

“Um...Bleak House I think.”

“Do you like Dickens?”

“Yeah man.”

“You don’t think he’s too sentimental?”

“What do you mean? Like affirmative culture for the Victorian era proletariat?”

“I don’t know. What did Adorno have to say about it?”

“Well didn’t Marx like Dickens?”

At a certain point it became clear that both of us had never read any Adorno or Marx on Dickens, let alone a word of the author himself. We shut the fuck up.

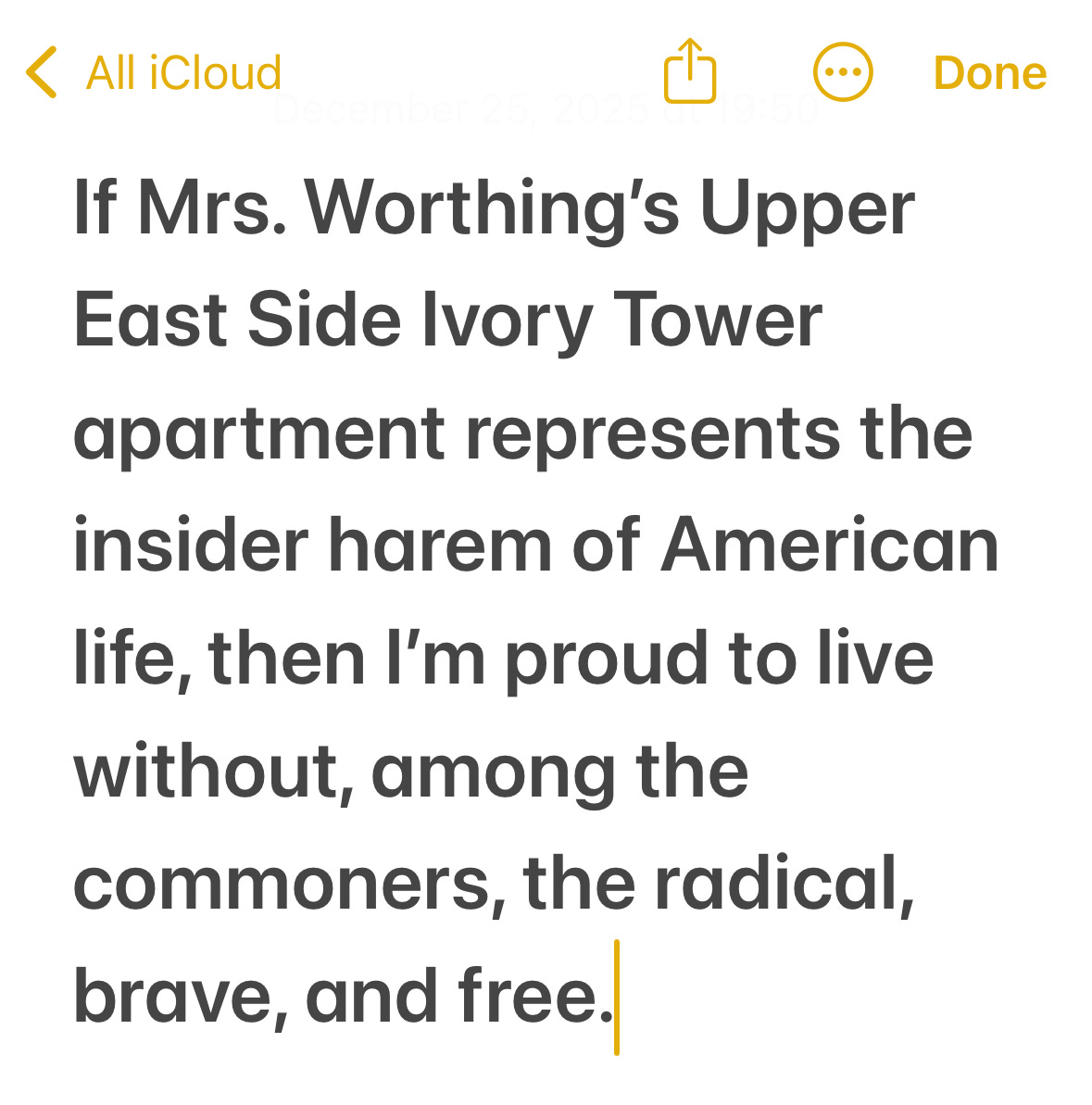

In part what I respected about the staffers at The Jacobin was their awareness of artifice. There was something both futile, vain, and noble about an independent socialist magazine at a tiny Berkshires liberal arts college. We all bonded around the idea that the meaning of our politics lay in the struggle to disintegrate the superstructures around us and reconstitute new understandings through praxis. We were an odd lot of nomads, blown by the winds of disaffection to the Left-most fringe. I felt a vague disquiet that should the breeze have gusted Right I would have found myself drinking whiskey and castigating the Woke mob with The Review through my college years. In a way we were all — Jacobins and Reviewers alike — part of the great unsheltered faction. The cyclone of modernity offered us no home except the alienated limits of the earth, so we wandered the great dunes together and formed our Bedouin tribes and rivalries by the costume of ideology. What force had spurned us desert-dwellers? I could never pin down a precise unifying principle. We came from all walks and strata, redneck and bourgeois and most shades in between. A good example of the type was a boy named Robbie Trapper. I thought Robbie was the cleverest guy who hung around The Jacobin. He was handsome and remote, and you could not trust him ever to complete an editorial task. Robbie told me once that sometimes he would wander into town at night and lie inside the dumpster behind the local supermarket. He wanted to know what it would be like, when he died, to decompose, to feel nature reclaiming his flesh.

“Fuck man, that’s fucking freaky man. I really don’t like that.”

“But that’s death. There’s something beautiful about the experience. I always start crying when I’m lying there in the dumpster. Slowly I strip away the layers of disgust. Then I relax, and I can see that the maggots too are living, feeling creatures. It reminds me that I’m alive, that I live once and only once. Then I’m gone. What’s so awful is what we’ve done as humans to destroy the natural state of these animals. The trash is this awful metaphor for technology. I’m vegan now for that reason.”

Robbie could never get out of his own way long enough to move beyond that hollow place; it wasn’t indulgence, and I never could discover the root of his despair. He was from somewhere in the Florida Panhandle — but that couldn’t explain all his discontent. Fucked-up parents? Probably. They had to be ultra-fucked-up though for their kid to hop in a supermarket dumpster swarming with maggots for the existential rush. Who knew what atavistic thing drove him to that trash heap? Robbie’s nebulous work ethic was really a shame though, he might have been a great writer if he had ever put pen to paper. The great help he provided to The Jacobin was a hazy repository of intellectual ephemera that he kept stored in his big-ass-head. Robbie would often hang around the office and function as a kind of perpetually stoned political theory archive.

One afternoon I consulted him about Worthing.

“You know what pisses me off about her?” Robbie said.

“Tell me.”

“I think she actually gets it. Or she gets it more than most people do. Have you read this essay on Trump she wrote in Freedom Magazine? It’s all about sublimation and de-sublimation. It’s really good. Like insanely clairvoyant. And sincere too. A deep cut, before she became a spectacle of the Right.”

Later that night I texted him.

When Robbie sent me the PDF, I stopped to read it on a bench by the moonlit Sparrow Pond. I had been out walking, trying to recalibrate my body and my brain after a lonely day spent cramming Worthing articles on my computer. The frigid wind had blown the last sickly feathers of fall from the trees. Now the pond had that spectral, skeletal look of winter. The howling landscape foreboded the marathon months to follow.

I emerged from the whirlpool of my phone to the arctic surroundings. I had the bends. My eyes telescoped between the moon and the lunar light mirrored in the silver water before me. I hated how I felt. I had stopped reading to discover that it was the real world which seemed to me the true simulacrum. What a fucked-up thing that device made me feel.

I sat there dumb, acclimating to the natural light. Worthing scared me. She was ravenous. A rapacious intellect, hungry to conquer. Earlier that week I had read an interview from a girl who had known the predator as a law school whippersnapper:

As I had grown more excited for our interview, doubt and ambition mingled and escalated in my thoughts like interlocking fugal phrases. I was a gladiator; I would soon grapple to death with a tiger in the name of glory. In the arena with that wild animal, mercy would be fatal. I now resolved, on that bench by the pond, that I would destroy Isabel Worthing.

I rose from my seat and went walking. The early hours of the night were crowding my mind with shadowy thoughts. I walked absent-mindedly and soon found myself on the far side of the Lawn, where the trees narrowed in on me and the path darkened. I knew where I was, for my unconscious had led me there. The gravel path steepened underfoot, and the night growled to me through the teeth of the trees. Above me a streetlamp glowed in just that spherical halo Worthing had described. I turned back as a spear of dread struck my chest. All was empty. The light summoned me onward, that ominous, milky light. I peered through the crevices in the trunks. I imagined a league of slender men in those woods, each disguised by their own pine, birch, or elm. And I could see her bare, innocent figure up ahead of me, pale as a ghost. She gazed back at me with terror. Was it I who had come for her, was it I who had chased her in pursuit? I wanted to tell her that I would not hurt her, but my voice could not reach her phantom. Why did she run from me? Could she not see that I had followed her here to protect her? Perhaps she could not see the look of care draped over my face. To her I was only another dark form come to haunt her, come to violate her cold and vulnerable body. She made for the woods now and disappeared between the trees. I only wanted to help. I worried for her in the cold. That translucent little girl in the sea of darkness. The fear of me would kill her. I followed her into the grove. She was such a strange, beautiful creature. Her elegant form flashed in and out of sight like a deer. And then it ceased.

I stopped there, deep in the thicket now, staring at the mute blue and gray apparitions of nature that loomed around me. I had crashed through the undergrowth, and my clothes were burred with thorns and leaves. I heard my rough breathing in the cold. What had come over me? Standing there in the woods, the scene of Isabel Worthing’s rape flashed all at once through my mind. Her face pressed into the wood — her jeans pulled down around her knees — her breasts exposed by her torn blouse. Would I have lusted for Isabel Worthing then? When she was a sophomore at Lyndhearst? She would have been a girl my own age, a girl with a movie star face (I had seen her yearbook photos), a girl with antagonistic politics and an indomitable mind. Maybe we would have forged a fearsome rivalry. I imagined her walking to class across the wintery Lawn, a short tweed skirt drawn over her black stockings and blacker boots. Her blonde hair skipping in the wind with precocious exactitude. Maybe I would have loved her. Maybe we would have made love. Maybe I would have wanted to rape her too. And would she have submitted to me instead of him? Would she have liked my white cock? Worthing had lied about the rape of course — I did not believe that that divine assault had taken place in the woods around me. Anyone from the Summit could have seen me retracing the steps of Worthing’s rapist. Were they watching me now? The news of my fantasies would spread like wildfire. Now I could not shake the image from my mind: Isabel Worthing was being raped before me. That young, headstrong girl, so resolute about her way in the world, so helpless in the grip of her violator. No matter how I tried to bury it in the night, the vision recurred. Maybe Worthing was right about what had happened. One of us was wrong. She could be telling the truth. No — I could not allow her fiction to cross my moat of antipathy. The rape was a straw man; I knew that. I was falling for her tricks, her paranoia, her violence, her deceit. Alhamdulillah. Are you fucking kidding me? I shook myself from the night terror and stumbled back toward the Lawn.

When I arrived home, Eve was asleep. I undressed for bed.

“Oh hi baby,” she said with tired speech as I climbed under the covers, “are you alright? Did something happen?”

“No — I’m okay. I was out walking.”

“Oh. Okay.”

“Is it late?”

“Yes it’s almost three.”

“What were you doing all that time?”

“I was thinking about the Worthing interview. I’m worried. Something is bothering me. I can’t track her down. She always slips away. I’m nervous when I get there that she’ll see straight through me.”

“No baby. Don’t worry. You don’t have to worry. You’ve prepared so well.”

“I know. But it’s something about her. She makes me so fucking angry. I can’t pin it down. When I think about her, I spiral to extremes. I hate her presumptuousness and her discrimination. I hate how she manipulates her followers. I hate that she seems to understand the situation. And I hate that she always comes to the wrong conclusions. I hate her greed, her mind...I’m afraid she’ll smother me.”

“Oh no. You don’t have to worry baby. It will be alright. Doubt is the natural feeling. But you have no reason to be afraid. I know she makes you angry. But the anger you feel now will settle into something strong. You’ll be confident because you’ll have already felt rage. She won’t be able to cut through to you. I believe in you Milo. We all do. We wouldn’t send you out on the assignment if we didn’t think you would succeed.”

“Okay. Thank you Eve.”

“A kiss for my services then. Good night Milo.”

“Of course. Good night Eve.”

One kiss, one pang of mortal fear, one soothing breast in my palm. I sunk into the perfect slumber.

When I woke in the morning, I remembered my episode in the woods and rid it as a dream, a fringe event, a flight of consciousness, a craving to glimpse the realm of the taboo, not to act inside it. When I reached for my sweater though, I found hundreds of flecks of leaves burrowed into the wool. I tried to pick them out, but there were too many. I wore a jacket instead. It was a crisp, blinding morning. A spritely blonde walked by me. Would you enjoy raping her too Milo? This girl or Isabel? Maybe both? No stop that. I had never had thoughts like this before. I asked for consent. I did not want to violate anyone. I had a girlfriend. I was a moral man. What was this evil thing inside me?

I decided on my way to breakfast that I was not a rapist. My thoughts were just my thoughts. The sweater proved nothing. I was not a violent boy.

There was one more stop I had to make before the operation: the office hours of Professor Angus Mills of the Lyndhearst Philosophy Department. I had taken “Introduction to Critical Theory” with the New Zealander my sophomore spring. Striding up the steps of the well-heated, faux-Tudor building, I knocked on Mills’s open door and watched his stubby, recumbent form assume attention.

“Oh hi Milo,” Mills said, his wide tongue working its way around his lips to lubricate the Kiwi accent that escaped like tobacco vapor from his throat. Mills hastily arranged the papers and books spread out over his desk. The tableau resembled how I imagine an anthropomorphic toad might live inside his tree stump. “How are things going? I haven’t seen you in ages.”

“Good! Yeah everything’s alright. And how are you?”

“Good. I’m glad to hear it. I’m doing well. Ancient as ever.”

“I’m feeling older too. Our class feels like quite a long time ago.”

“Well you’re young. Class feels like yesterday for me. I’m in the bottom half of the hourglass.”

“Well I’m here Professor Mills because I was doing some research on Isabel Worthing in Draper Library, and I came across a culminating experience she had completed her sophomore year — about Nietzsche — which she wrote for you, for your seminar on ‘Philosophy in History.’”

“Yes.”

“Well I wanted to talk to you about her.”

“About Isabel?”

Oh so she was Isabel to Mills? Well I guess there was no reason she should be Worthing or Mrs. Worthing either.

“Yes.”

Mills got up and walked to the entrance of his office. He kicked away the door jamb with his loafered toe, shutting us in. The gray sky and fractal branches outside his upper-story window swirled with academic, autumnal severity. The law required that Mills should now utter a grave or enigmatic thought.

“Isabel is tricky for me to discuss. What do you want to know?”

“I want to know what she was like as a student — how you think she ended up where she is now?”

“Yes?”

“Well you taught her?”

“Yes I did.”

“Go on.”

“Isabel was here in the early nineties. I was new to Lyndhearst. I was an adjunct then. I think I was twenty-eight when she enrolled in my seminar.”

“And what was she like when you taught her? Was she a controversialist?”

Mills’s eyes had wandered off to the window, and he turned to face me when I spoke, as if all at once remembering my presence in the room.

“No — what? Isabel wasn’t a controversialist. I’ll speak frankly with you Milo because I know you understand these sorts of things: there are students who get the material and there are students who never will. Isabel was very young and very hungry. She could compute and reconstruct the texts instantaneously. And she was utterly obsessed with the principle of application — she would come to every office hour I hosted and ask me questions about praxis that I was completely unprepared to answer. She’d follow me to my car until I demanded that she leave me alone. She wanted the answers. I pointed her in certain directions. Ideological directions beyond the scope of what I thought acceptable for class. The kind of material you wouldn’t teach for fear of indoctrination — you understand — because I worried as a teacher that I could not properly relay the danger of their arguments to a class of fifteen or twenty. All the critical theory we read together in class that spring has a dark side you realize Milo? Enough curiosity and one is led to dangerous places that they probably should not go without caution. Isabel was that way. Too eager, too expectant that ideas had solutions. We developed a very intimate intellectual bond when she was in my class. She kept in touch afterwards. She planned to assign me as her thesis advisor. And then one winter she stopped coming to my office altogether. I’m sure you’ve read the news and the excerpt of the memoir.”

“So you believe the account that she gave in My Bravest Years was true?”

“Who am I to say? How would I know?” Mills almost yelled, his eyes fluttering madly about the ceiling. “I’m sorry for raising my voice Milo. But I feel I shouldn’t be discussing this subject with a student. It’s inappropriate for me to speak about Isabel and the allegations. I’m sorry to disappoint you.”

“No no I understand Professor. I’m prying.”

“No it’s not that Milo. It’s my own problem.”

“I understand. I’ll let you be. Have a nice evening.”

“Thank you. I’m quite sorry for reacting this way. Good luck with the end of term. Come by again sometime and we’ll have a proper chat.”

Mills averted his stare, nibbling on his bottom lip and folding his hands together in a tremulous web. In his mind, I had disappeared; he didn’t hear me when I spoke to him.

“Thank you Professor. I will.”

I walked down the stairs with startled breath and a grin of incredulity. God the Philosophy building was hot as a sauna; my cheeks were flushed. What the fuck had gone on back there? Why had Mills turned sentimental on me? Maybe he was wistful about his mistress, his protégé. Maybe he missed his Isabel. Maybe he regretted letting her get away. Whatever their relationship, Mills provided me with a drawbridge into the fortress of the Worthing psyche. Something must have happened between them for her to ghost him. I filed the secret passage away for later use. At last, between the armor, a sliver of flesh.

“I think the strategy has to be disarm, excite, agitate, kill,” Julian told me that final night in the newsroom, gesticulating his intentions like a general might direct an army.

“Alright. So let me run through the sequence...hook Worthing with Reviewer flattery...then I challenge her with friendly Socratic questions while the tape is rolling...I close the interview and make clear to end the recording...ask her the real shit off the record when she’s warmed to me...and all the while I’ve got a second tape secretly recording the responses.”

“Yes yes exactly, you have to convince her she’s in the company of a confidant. Then at the end you can let it unravel a little for some rawness. Just take my phone and keep the voice memo running the whole time.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes it’ll be no problem.”

On the eve of the operation, I rehearsed the possible sequences and permutations of our encounter a thousand times in my head. I would say one blistering comment, Worthing would parry. I would set another delightful trap, Worthing would dodge. I would hook her on a final question, Worthing would incriminate herself and admit defeat. The role play was wonderful until it soured into nightmare. Worthing would sniff me out, Worthing would humiliate me, Worthing would stun me with a dexterous response. I would agree with her. Her persuasion would arouse me. I would sit paralyzed as my erection grew to titanic heights, in awe of her rhetorical prowess. Worthing would take off her top, revealing her motherly breasts. I wouldn’t be able to resist her, that horrific lascivious succubus. I would have sex with the woman I hated the most in the world. I would like it. I would scuttle back home like a beetle. Eve would castrate my manhood with her teeth as punishment for emotional and moral disobedience.

I got up that morning at five for the coach at six. I had no problem waking — I had hardly fallen asleep in the struggle of those dreams. I made up for lack of rest in store-bought “espresso-and-creams.” On the bus to Manhattan, I listened to Playboi Carti as dawn crept like noxious rosy gas through the Berkshires. Then I played Jackson Browne’s “These Days” on loop as the interlocking evergreens and suburban refuse shuddered through my vision.

I took off my headphones when the sun was up and read through my notes for the interview. In the lowest sense, I felt wholly prepared; I had done my homework. In the highest sense, I was horribly unprepared. I would have to do at least a decade more of living to get on her level. I looked up from my journal as the great city crawled to form around me and the semi-natural world bled to artificial symphony. The glass-and-steel titans of Gotham smothered the horizon; the skyscrapers crushed me with their totality; they infused my mission with the ultimate triumph, the ultimate horror.

In the lobby at 130 East End, a marble-coated space of the pre-war vogue, I told the doorman that I had come to see Mrs. Isabel Worthing. He told me to go right ahead. The elevator held within a second doorman. Which floor? he asked. Oh the eighth floor, Mrs. Isabel Worthing. My god — what was happening? What century was I in? The elevatorman rolled closed the cage to deliver me skyward.

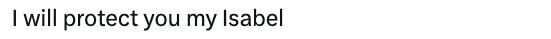

When the bell from the lift announced my arrival, I checked my notifications one last time. Eve had texted —

— Foucault’s Discipline and Punish rested against her pale Regency breasts. There was a little flower sitting in a pot on the table in the hall. It was all ironic, it was all serious. But there was no turning back: I now watched the world collide in Isabel Worthing’s atomic eyes. She was waiting for me to speak.

“There’s been quite a lot of talk recently about your role with the College, especially considering your resignation from Lyndhearst activities last week. Some see you as a potential candidate should things fall through again with another president. You’re a woman and an alum. Would that excite you, being president of Lyndhearst?”

“What has my being a woman got to do with being president?”

“I only mean that Lyndhearst — historically an all-girls’ college — has a long lineage of woman presidents.”

“Oh I’m kidding Jack. I know what you mean.”

“Forgive me.”

“Yes — president does excite me. I think I would do a great job. I think the College is in a difficult place after so many years of ethical and academic erosion. We’re seeing now with President Larson, who is a fine and decent leader, that Lyndhearst needs energy, conviction, and direction, not just steadiness.”

“Well we will cover the international student question, I assure you, but what would you envision for Lyndhearst?”

“What do you mean precisely? I have an answer, but it’s quite mystical.”

“Well start there. I think part of the reason we’ve ended up where we are now is an estrangement from that mystical idea of what makes the College extraordinary.”

“Well you understand in part Jack, you’re there at Lyndhearst now — but the miracle of the College is the fusion reaction that goes on on campus between security and challenge. Because the school is so small and interwoven, students surrender themselves to the traditions of the College, one of those traditions being rigorous learning, and — having stripped away any artifice through intimacy — the pupils and professors can then freely engage in truly difficult, generative discourse. The intellectual culture at Lyndhearst, you’ll soon learn in the outside world Jack, is as rare as rare comes. But those principles — security and challenge — those principles have slipped over the years. They’ve been eaten away by miserly practices; policies that once looked ripe and promising for the Board but now show real signs of decay. It really started when the Asian students first arrived on their private jets from Beijing with three-million-dollar donations in their carry-ons. The College could not have been more ecstatic. Then they got greedy, the money-laundering ran rampant, and now the administration can’t operate their financial models without that miasmic income stream. Meanwhile these alien students leech off the Lyndhearst prestige while corroding the very intellectual environment that lends Lyndhearst its reputation in the first place. They don’t care about America, about American values, about the progress of the American project. They only care about the degree. And often you’ll end up — for instance — with something like a queer Marxist from Turkey whose father is Erdoğan’s Minister of Health. And it’s this person who wants to disabuse the promising Americans of their exceptionalism that they learned as children of this great land. It’s this person who says to their friend — ‘go ahead, get polemical, hunger strike for Gaza’ — because a starving student in Lyndhearst can solve the Middle East. They don’t have a stake in our country. They’re going to go right back to their villas in Cairo or Shanghai whenever they get their hands on a diploma. I really believe its these foreign students and the faculty who conspire with their agendas who need to go if we want to start to rehabilitate Lyndhearst as an elite American institution. You’d never get the situation in the President’s Office last year if students weren’t being taught Frantz Fanon in half their classes as the messiah. Lyndhearst needs a facelift, like a grand old palace that has fallen into disuse. You can see the values remain, I mean look at the seriousness of The Review. Lyndhearst needs a unity of purpose though — I think the students just don’t feel safe anymore, they don’t feel safe to be or to challenge or to commit to their pride — you see it in my rape, in the incendiary protests of last year, in that atrocious incident with the Jacobin editor. Bringing Lyndhearst back involves real commitment to safe expression and open debate. I mean look what happened to Charlie Kirk. How can you rebuild a culture of intellectual confidence in that hostile environment? Well actually I want to know how you all are responding to the assassination.”

“I mean we were all so shook. Our Review group chat flooded with messages. Mostly grief. And a lot of anger. Now there’s a movement to open a Turning Point chapter on campus.”

“That’s good then. So there’s motion at least.”

“Yes. We held a well-attended vigil on the Lawn. I encountered a lot of respect on campus actually, contrary to the despicable things I was seeing online. Charlie was kind of our generation’s guy. They kill your prophet and that freaks you out. It all felt very calculated, very political. The Left sensed that too — that everyone should be afraid, that things were getting out of hand. Well how do you feel about his murder? You’re a public political figure. Does it scare you? Do you ever fear for your life?”

“Yes. I do fear. I get death threats all the time. Before Charlie’s killing, the attempts on President Trump — even the United Healthcare shooting in Midtown — I think I was able to dissociate the rhetoric from the fear. I knew all about the entropic spirit of the American Sixties, you know, I knew the assassins were lurking there in the underground, but I could separate the online anxiety from my tangible reality. That’s been ruptured for me mostly, though I still feel safe. Since my campaign I’ve lived a rather private life. But the threats are tinged now with the paranoia of credibility; stuff about my kids, my husband, horrible things that these psychos would want done to me. I mean just last week, after the memoir was published, I received dozens of violent messages. Things like: ‘I don’t believe you, you mendacious cunt. But I hope that it’s true. You’d have deserved it.’ We don’t live inside the same country as those people anymore. The internet has totally degraded the collective reality. Everyone lives in their own fragment of truth. These people spiral into their cataclysmic silos — it’s total informational anarchy — so yes I believe that someone would be crazy enough to kill me. That their hatred of me would echo loud enough to silence any rationality. And that they would resolve that the best telos for themselves would be to hunt me down and eliminate me to prevent an apocalypse. I can imagine that timeline with ease. And yes — it terrifies me.”

“And now in New York with Zohran in charge too —”

“Don’t even get me started with that commie —”

“Well do you ever feel the same as those people? Like the apocalypse is imminent? Like only something extraordinary, something extreme could stop it? I think it’s a natural human instinct. I think that’s why it’s so hard to police.”

“Of course I do. That’s the modern condition. Overwhelm. Confusion. Chaos. Fragmentation and fracture. I agree that abandon and adrenaline are natural if you see a train hurdling down the track at your bound body. You’d do anything to free yourself — the threat of the inevitable can bring out wildness in anyone. You’d bite off someone’s face — in fact you’d shoot their head off with a hunting rifle at a campus event — if you could only emancipate yourself from certain societal decline. Issue a warning. Become a martyr. But I think every worthy thinker realizes that violence in any circumstance can only function as a catalyst for vengeance and retribution. I believe in a kind of personal political isolationism.”

“And what do you say to those critics who would say that your style of politics accelerates the train, speeds up this kind of informational disintegration as you said?”

“I resent your implication Jack.”

“It’s not my implication, it’s the implication of your critics.”

“I think there’s a right and wrong direction for our country. I think my critics accelerate decline through lies. I think I try to realign America with the truth.”

“I think they’d say the same.”

“And they’d be misleading. That’s disingenuous.”

“Well what about the second principle you described? We talked about security. I believe your second principle was rigor —”

“Challenge.”

“Challenge yes. What would say about the resurrection of that value, in terms of Lyndhearst policy?”

“Well I think the goal posts have moved dramatically for what the model for academic work should look like in the 21st century humanities. In my era of Lyndhearst, there was great honor in being considered a literate, sophisticated, erudite person. As a school you have to incentivize education, you have to create a social milieu that worships the learned archetype. Incentivize education and students will educate themselves; incentivize beauty over ugliness. But the instruction has fallen woefully behind with the realignment of these incentive structures. For instance, when I was at Lyndhearst we had to use a card catalog to find information on a subject in the library. Now you all can synthesize any number of texts without doing any reading whatsoever. AI use among your generation is more epidemic than any elder could fathom. Adults who overlook the technology are behind off the bat — so many professors are trapped back in medieval times when rote memorization and analysis constituted a viable strategy for learning. This is part of the work I was doing with the American Values Board that I was chairing. I won’t reveal too much of our private deliberations, but so many of our findings consisted of exposing inconsistencies in how classes were being taught versus the sorts of learning practices the students were engaging in. In my age there was certainly cheating — but there was at least a little effort involved in the reading, writing, and transcribing that cheating required. All of that is out the window. So we have to learn as a college how to re-acclimate our students to an environment of active engagement and generative thought. That means reorienting the kinds of tasks that we assign. It involves upending the entire status quo of the classroom and the curricula. These professors will have to get uncomfortable too. The students feed on the laxity of their instructors, their arcane assignments. And we also have to root out dogma and false pluralism from the system entirely. We need to be having honest, discursive, heterodox conversations. Not just echoing the liberal talking points of a socialist commentator who spent their adult life in the prison of a grad school. The meritocracy has made huge strides from five years ago when we had reached the nadir of DEI. The shift is real. As a school we have to work every day to extinguish mediocrity — it’s too easy to lapse into the average, the boring. Well here’s a question for you Jack, do you use AI for your assignments?”

“I’ll be honest. Yes I do. I try to use it sparingly — but the temptation is too strong when the professor assigns something idiotic like you said — an old-fashioned problem set or a simple textual summary. I’ve been assigned those archaic homework problems in the last few months even, problems these models can solve with copy and paste in less time than I could read the text of the question. And I agree — the problem is that the incentive structures are so completely out of whack. I mean if you’re after a grade as the ultimate achievement — over the learning — then why not use these tools to your advantage? You’d be a fool not to. The College just seems so ill-equipped in its present form to act nimbly. It’s so bureaucratic and the practices are so arcane. I don’t know how it will calibrate to the new landscape before the technology steamrolls it again.”

“And how do you find your attention?”

“You mean how well I can focus in class?”

“Yes — for instance how much do you find yourself reading?”

“I enjoy reading. But sometimes I find the distractions at school insurmountable. I don’t know if that’s a generational problem though or a perennial struggle of the college undergraduate.”

“Well I’ve found that there’s at least some leakage between the classical education we received at Lyndhearst in the Nineties and the canon you read today.”

“Yes?”

“Well my freshman year when I took The Core we read thirty books.”

“Yeah that’s unthinkable.”

“And none of it was any B-rate revisionism: all heavy-hitters, all great books you would proudly display behind your desk on a pandemic-era Zoom call so you could puff your chest out and beat your breasts when someone asked — ‘Oh is that Middlemarch I see?’ I mean it was extraordinary. It defined the Lyndhearst pupil. It was Lyndhearst’s finest achievement — it really allowed me continual faith in the school because I believed in the great books — in that whole philosophy. We all would compete over the material — if you didn’t read the texts, you were a total philistine, you were an unserious person.”

“Wow. I think we’ve departed quite a lot from that kind of model. For me the question has become: why should I even read a five-hundred-page book for class when I’ll speak for sixty seconds total in the seminar? Half the time we never talk about the text — we talk only about the extratextual history and theory swirling around, I don’t know, Poe or Hawthorne. So why not read the other book that I’ve been wanting to start for a week instead? Why not go party with my friends while we’re young? Why not do literally anything else but my classwork? I don’t think it’s something broken with me or my classmates. But it’s the feeling that something is wrong with the whole institution of humanities education. That something about the internet and AI has neutralized the immediacy of any reward for doing the reading — indexing information, becoming read — those things don’t seem to matter — or they still matter but are no longer urgent. To choose to be a Philosophy or English or History major these days is a much more mystical, metaphysical statement about the aesthetic practice of living than about educational cost-benefit analysis. Or it’s just laziness. Usually the only thing that keeps kids reading for class is some residual psychological obedience to discipline or duty. It shames me to imagine an honest conversation with my parents about what their thirty-thousand-dollar checks go toward. In my opinion, someday the floor’s gonna fall out on the whole mirage. I mean I had a professor who would often ask our class, ‘have any of you read any Joyce, any Henry James, any Mann?’ It’s always silence — including myself — I haven’t read any Joyce or James or Mann either. And he’ll say — ‘what are they teaching you all at Lyndhearst anyways? These are the core texts of the Western tradition, come on!’ — with a jovial and melancholic dismissal. And the class will croak and squirm in their chairs because we know in some way we’re failing him — this jurist of high culture. Whether anyone will care about that failure in the long term, I don’t know. That old canon you read back then is dead though.”

“I don’t know either. I don’t choose to accept that it can’t be resuscitated. And I can’t help but blame in part the systematic dismantling of the canon that the gender/race studies people did to desecrate the holiness of these texts. Look what they did to Conrad! It’s patricide. Which professor was that, by the way, the one who challenged your class on the canon?”

“Professor Angus Mills of the Philosophy Department.”

“I don’t know him.”

“He might have been around actually when you were a student. He’s been teaching at Lyndhearst for thirty-five years I think.”

“And Professor Mills is one of your closer advisors?”

“Yes I’ve grown pretty close with him. He doesn’t teach in my major department though. I took his critical theory class last spring.”

“Yes — maybe I do remember Mills — he resembles something like a frog.”

“Yes! I’ve had exactly the same thought before.”

“Must be the same Mills. Yes I took a seminar with him called ‘Philosophy in History.’ He was very young then. Fresh out of his PhD. A little watery, very ambitious — so was I.”

“I thought so. I was doing some research on your old Review articles in the archives at Draper —”

“Oh god. Don’t remind me. I’m so embarrassed of all I wrote in college —”

“No! I thought they were magnificent. The most cogent and vivacious writing I’ve ever read in a college magazine. The work is usually so milquetoast or unrefined.”

“Well thank you. But I don’t believe your flattery.”

“You should. I thought they were extraordinary.”

“What else did you uncover from my past?”

“Well I came across your culminating experience for Professor Mills’s seminar. You wrote about Nietzsche.”

“Did I?”

“Yes.”

“It was called — ‘The Moral Master.’”

“Oh no! I don’t even remember writing that. I must have been talking about ‘On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life.’ I don’t want to imagine what trite thing I might have said. Did you end up reading the essay?”

“Only your introduction — the library was closing when I discovered it.”

“Oh that’s good. But what a shame, it probably would have changed your life. I’m kidding, but that Nietzsche text would be important if you’re wanting to be a History major.”

“I haven’t read it — I’ll take a look.”

“Have you ever spoken to Mills about me?”

“No. I haven’t been to his office since the term began.”

“That’s good, I don’t think he would have the kindest words for me as a student — well can I ask you what you thought of the critical theory as a conservative? I imagine Mills taught the course with a fairly liberal bent if he hasn’t changed since I knew him. Although I know a number of Mills-types who have tacked Right.”

“Yes he definitely taught with liberal bias — but I think he’s tremendously charitable to the counterreaction. And I actually think those Frankfurt School thinkers offer quite appropriate diagnoses for the modern condition. I had gone in with an adversarial expectation — really the answer to the Enlightenment is socialism? — that kind of thing you know? But that wasn’t my impression at all — my treatment of Adorno and — and — what’s his name? — whatever — was quite different when I left the class. Why do you ask? What was your relationship to it?”

“Well what you say is right. I think the most overlooked part of a serious thinker’s education is the thorough understanding of what impulses and arguments exist in their enemies and rivals. Empathy for evil —”

“I completely agree.”

“I mean Jack I read all the Frankfurt School stuff around the age that you are now. I devoured it. I couldn’t get enough. I felt it held within its language — within the web of its references and vernacular — the answers about how to live. That’s what I was after really when I was twenty or twenty-one: the answers to why it was I felt so alienated, so alone, so out of sorts in the present — I wanted the cure. So I read it all — it’s probably the most honest, most rigorous, most intellectually systematic approach to modernity — and I reached the end, and I looked around myself and thought, damn I am miserable. I was really dissatisfied. I was more cynical about the future than ever before. I was unhappy with myself and my life and my country and my era, and I decided that the Frankfurt School wasn’t enough for me. It couldn’t be enough. I could not accept it as the schematic for life. It was too gray, too meaningless, too morbid. I could not allow that to be the end. I really went through a period of extreme nihilism after that. Too much thinking can be bad for you, too much thinking can lead to a damaged life.”

“And what about Mills? Why would he have unsavory things to say about you?”

“Well I think I pushed him past the limit where he felt comfortable as a teacher. Into a realm that he was still sorting out for himself — deciding for example how attractive things like fascism or anti-democratic government really were as an alternative to the present situation. Things he would normally never have discussed with a student. Things he didn’t want to discuss with a student. His ideas were inchoate. But they were places I forced him to go with me.”

“And — if I may ask — when did the assault fall in the timeline of your intellectual development?”

“I’d rather not talk about my rape on the record.”

“Okay. I understand. Well can you say a little more about what happened after your period of nihilism? How did you snap out of it?”

“Well I didn’t know what I was going to do. I spent a long time fantasizing about dropping out of college. I had dreamed of walking across Europe. But I decided it would be too dangerous a journey to embark on alone as a young woman. I had other wild ideas of roaming Germany and Austria and Switzerland and the Netherlands, making pilgrimage to the great churches and Alpine birthplaces and weathered gravestones of the pan-Germanic writers and composers and painters I had fallen in love with in my lowly New England.”

“And you went?”

“Well yes but not without difficulty — I writhed my way out of obligations somehow and took a semester away from Lyndhearst. I flew to Vienna against the orders of my parents. Thankfully they were worried enough about my mental state that they lent me money to sort myself out. I ended up a month later having a kind of revelatory experience at the Berlin Philharmonic listening to Wagner’s ‘Tristan and Isolde.’ I was really quite overwhelmed. I was overcome with this boundless sense of pride and nostalgia. But I realized that the fervor that stirred in me at the symphony was not a nationalist urge for Germany or Austria — I learned quickly that those places were certainly not my true Vaterland — the ecstatic feeling was really a love for my United States, a latent patriotism that was only activated by traveling the rest of the world and seeing how good I had it back home. Then I got very anxious. I doubted constantly that my life would amount to anything significant. The world plowed on around me, and I stood like an ant in its wake, helplessly distracting myself with a crumb before I drowned in the cold sea of oblivion. I refused this fate. I was so ambitious after all! I walked by Bismarck’s statue that night I think — in the Tiergarten by the Victory Column and thought: that’s the kind of life I want to live. I decided that the worst thing would be to disappoint myself, I would not be passive. And if I weren’t to submit, then I would need a purpose, and so I planned how I would execute my climb up the peaks of influence and power in America. I resolved that law school, Harvard Law specifically, would be most useful to me as the first rung on my ascent. I was very calculated. I wanted a say, I wanted to steer the USS Columbia homeward, starboard. I wanted power — I’m not ashamed to say that. And the LSAT was just another test after all. Something to be puzzled out. Something conquerable. Homework always came easily to me. I got into HLS. And it all followed from there.”

“What’s your relationship to Germany now — bitterness?

“No it was never bitter.”

“So you go back often to Europe?”